| Voir le sujet précédent :: Voir le sujet suivant |

| Auteur |

Message |

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Mar Fév 10, 2015 13:57 Sujet du message: Des avions dans le ciel d'une Sibérie uchronique Posté le: Mar Fév 10, 2015 13:57 Sujet du message: Des avions dans le ciel d'une Sibérie uchronique |

|

|

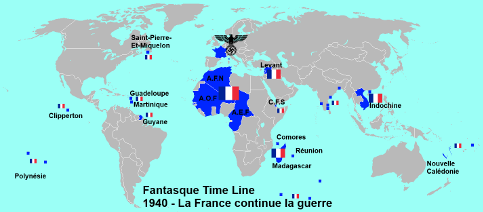

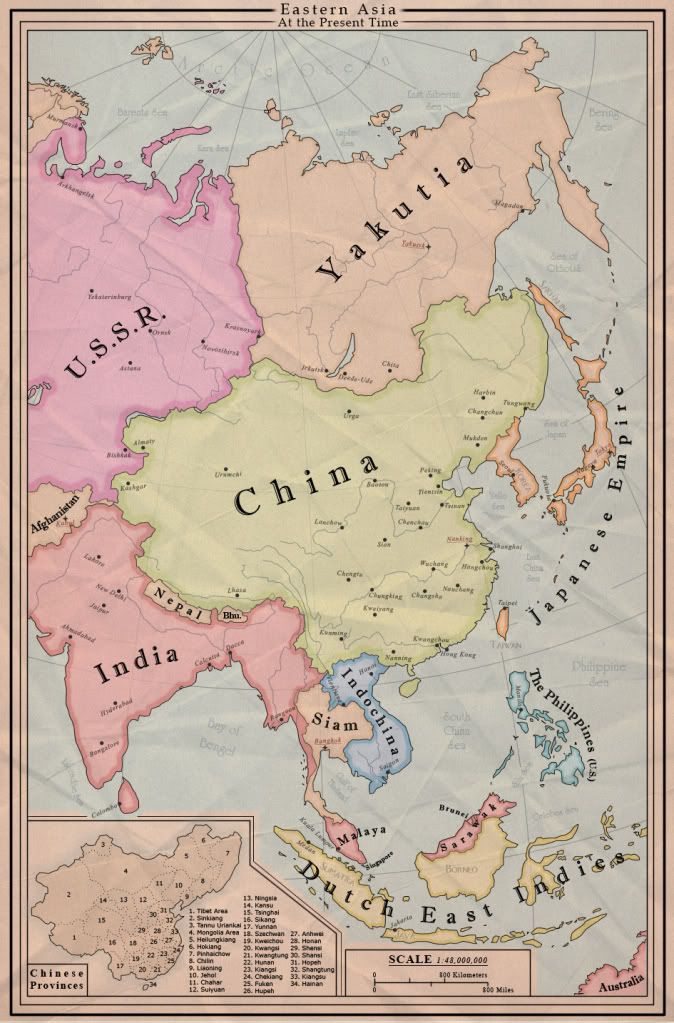

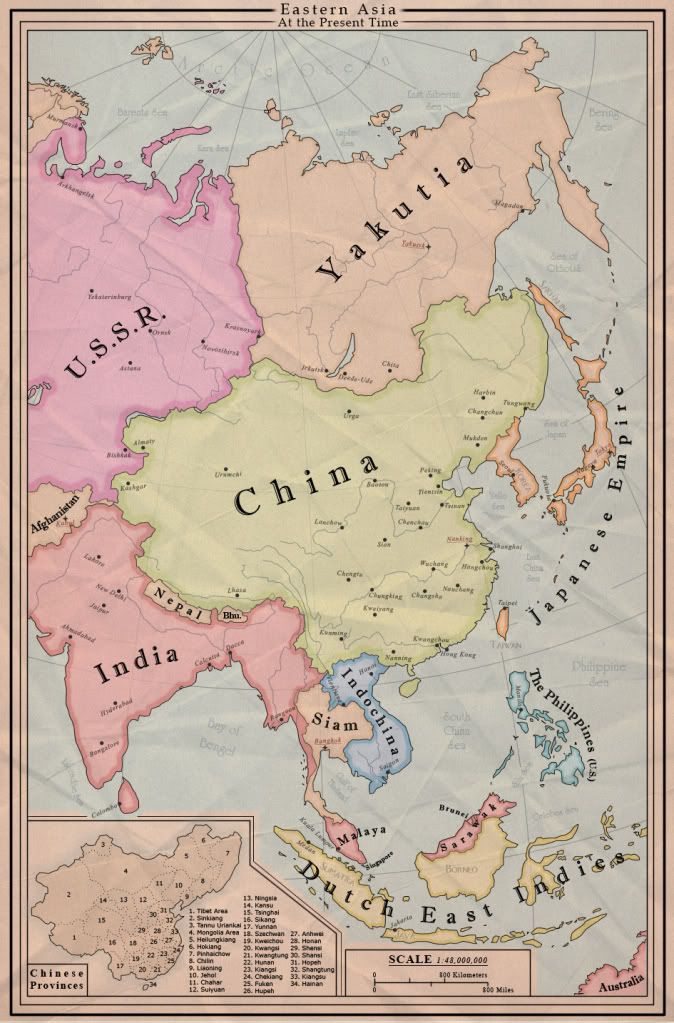

Comme le savent Casus et quelques autres, quand je ne contribue pas à FTL, j'écris (à un rythme d'escargot) mon uchronie personnelle, "With Iron and Fire". Le point de divergence est la mort prématurée du président provisoire de la République de Chine en février 1912, mais une partie importante du projet concerne la création d'un Etat sécessionniste en Sibérie orientale au cours de la guerre civile russe. (Tous ceux qui ont envie de lire l'ensemble de mes travaux peuvent le faire sur WIAF ou, pour ceux qui en sont membres, AH.com).

Ce qui suit est l'histoire de l'aviation du nouveau pays en question, la Yakoutie.

Tous les commentaires sont les bienvenus; j'ai déjà mis Casus à contribution pour la relecture, mais il ne s'agit pas encore de la version définitive.

***

Reaching for the Eternal Blue Sky :

A History of Aviation in Yakutia, 1917-1945

1917-1922

Russia’s entry into the age of aviation took place on 25 July 1909, when a Dutchman, Baron Alexis van den Schrooff, flew over Odessa in a Voisin biplane; this was less than two months before China’s own aviation first, since Feng Ru made his historic flight over Oakland on 22 September of the same year. Then on 23 May 1910, a Russian-made airplane took to the air for the first time near Saint Petersburg. Coincidentally, one of the pioneers of Russian aviation was from Irkutsk and would later become a Yakutian citizen: Yakov Gakkel, an electrical engineer, designed some of the first Russian-made aircraft, though his workshop proved a commercial failure and went out of business in 1912 (he would move back to his native Siberia during the civil war and eventually become chief engineer at Bryner, where he was a key contributor to the development of the company's trademark screw trucks). In the years leading up to World War I Russia started catching up, and even became an early leader in multiengine aircraft when Igor Sikorsky designed the Russky Vityaz, the world’s first four-engine passenger plane, later to evolve into the heavy bomber Ilya Muromets; but even with a rapidly expanding domestic aircraft manufacturing sector, it remained dependent on foreign—mostly French—powerplants. By the beginning of the war, the Russian Air Service had the world’s largest air fleet with 244 aircraft (224 of them French-made), but in the course of the war this early advantage was eroded by its aviation industry’s inability to cope with high attrition rates. Engines, in particular, were in chronically short supply. Russia built 400 aircraft a year, compared to Germany’s 1,348, and with the constant losses only fielded 579 by December 1917, with an extra 1,500 in various states of repair, storage, or training use.

Between the Bolshevik takeover in November 1917 and the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk the following March, the Russian Air Service—along with the rest of Russia’s military—ceased to exist as an organized body. With no orders, no command structure and no pay, most Russian pilots and ground crews simply went home when they were not summarily executed by revolutionary soldiers’ committees, so that when the various factions that would fight in the Russian civil war coalesced by June 1918, the Bolsheviks found that they could barely scrape together some 150 aircraft. The various White armies were even worse off with a few dozen aircraft each: when General Horvath set up the Provisional Siberian Government, he had at his disposal 65 aircraft and slightly more pilots.

The first deployment of aircraft in the Siberian Campaign was on 18 March 1918, when a single Caudron G3 observation plane was sent ahead of the Chinese Seventh Cavalry Regiment, on a reconnaissance mission over Blagoveshchensk (two days later, another observation plane was similarly sent ahead of the Fifth Cavalry Regiment over Khabarovsk; neither was armed). On April 2, when the Chinese Eight Infantry Division entered Vladivostok, it was accompanied with a flight of three G4 aircraft; although these were likewise primarily assigned observation duty, they came with ammunition and ordnance in case they might be called on to actively engage enemy targets.

By June, the Chinese Siberian Expeditionary Corps was assembled, though between the hurdles of deployment and the fact that the front was thousands of kilometers to the West, it only saw small-scale action, mostly of the counterinsurgency kind against bands of Red partisans, until the Battle of Perm in December. Its air component, under the command of newly-promoted Colonel Rong Zhen (one of the so-called “Eight Immortals” of Chinese aviation) was composed of two squadrons, one of Farman F-40 observation planes, the other of Voisin VIII bombers. Chinese airmen first shed blood in Siberia on 23 August 1918 when a F-40 strafed a group of partisans near Kansk, while on patrol along the Transsiberian railway, though they already had received their first non-combat losses weeks earlier, when a Voisin VIII crashed while attempting to land, killing both crew members. At the Battle of Perm, on 15 December, Colonel Rong’s forces took part in the campaign’s first air-to-air battle: a flight of four Voisin VIII bombers on an air support mission were engaged by two Bolshevik Nieuport 17 fighters, which downed two planes and damaged a third before breaking off unharmed. These were the only two airworthy fighters available to the Bolsheviks on that part of the front, yet they had achieved a clear tactical victory over the CAF. Stung by the humiliation, Rong requested from CAF commander General Feng Ru, and swiftly obtained, a large overhaul of Chinese air assets in Russia: in January 1919 the Expeditionary Corps’ air strength was increased from two to eight squadrons (including three of fighters—two of SPAD S-XIII and one of Sopwith Camels) organized in two groups. It was further expanded in March with the addition of another group of four squadrons (one of SPAD S-XIII fighters, three of Breguet 14 bombers), in preparation for the forthcoming Volga Offensive. Its size would be further increased throughout the following three years, so that by the time the Campaign ended in 1922, it comprised no fewer than 13 groups.

The air forces of General Horvath’s Provisional Siberian Government underwent no less impressive an expansion in the course of the conflict, officially known in Yakutia as the War of National Independence. As previously mentioned, at the time of its foundation it only had 65 aircraft in varying states of airworthiness: an assortment of older Nieuport, Farman and Voisin planes, mostly imported from France though a few had been assembled in factories in European Russia. This disparate collection was organized into a coherent fighting force under the energetic leadership of Colonel Igor Shangin. The son of a civil servant in Irkutsk, Shangin had risen to the rank of captain in the Transbaikal Cossack cavalry before the war. In September 1914, he had transferred to the fledgling Russian Air Service; in 1915 he had studied at the Military Aviation Academy in Sebastopol; by June 1917 he was deputy commander of Russia’s First Air Group. After the Bolshevik took over, he sneaked out of revolution-wracked Petrograd, made his way back to his native Siberia and put himself at the service of the PSG. General Horvath put him in charge of “everything that flies under Russian colors east of Sovdepia”. “Sovdepia” was the derogatory term used by Whites to refer to the area under Bolshevik rule (the Bolsheviks, for their part, derisively referred to PSG-controlled Siberia as “Happy Horvathia”, which before 1918 was the nickname of Horvath’s China Eastern Railway satrapy).

It was a thankless task at first. Spare parts, and especially engines, were difficult to obtain, so that at any one time nearly half of the PSG’s small air force was grounded, awaiting maintenance; to deal with logistical issues, Shangin drafted Aleksandr Friedmann, former manager of Aviapribor—a manufacturing plant of aircraft component parts founded in Moscow in Summer 1917—who had escaped revolutionary turmoil by taking up a teaching position at the University of Perm, where PSG forces found him in December 1918 [1]. Training new pilots to increase the roster beyond its initial size of 70 was also a challenge. This pressing problem was solved when Aleksey Abakumenko and Stepan Nozdrovsky reported for duty. Abakumenko, initially an airplane mechanic who had become a pilot, had had the good fortune to be sent to Britain to study at the Royal School of Aviation mere days before the Bolshevik takeover; returning to Russia via Vladivostok in August 1918, he was entrusted with setting up a flight school in Irkutsk. As for Nozdrovsky, a former mathematics lecturer at the University of Saint-Petersburg, he had obtained a pilot’s license in 1913 and become a flight instructor. A fighter pilot on the Eastern Front, he had moved to Kazan after the collapse of the Russian military structure and opened a private flight school; when the Czech Legion took the city in August 1918, he joined the PSG and by September was in charge of the new Chita Flight School, later to become Chita Air Force Academy.

Most importantly, the taking of Kazan also gave the Siberian Whites the fallen Tsarist regime’s gold stockpile, making it overnight flush with hard cash—even after the Chinese had taken their share and various higher-ups had duly lined their pockets, that still left Horvath’s government with over 300 million gold rubles. Then, three months later, Germany surrendered and World War One was over, prompting Entente governments to abruptly cancel wartime orders to their respective defense industries, leaving the latter with huge amounts of unsold inventory and idle production capacity. Urgent demand met eager offer, and by the last days of 1918 freight ships were sailing from Western Europe to Vladivostok, loaded with all manner of military supplies, including aircraft both surplus and fresh off the factories. China, of course, did likewise with its own share of the windfall, and other ships sailed bound for Tianjin and Qingdao. The first deliveries in February 1919 coincided with the graduation of the first batch of Chita and Irkutsk Flight School graduates, and Shangin’s air force swelled from one to three groups, now equipped with the latest types of aircraft: SPAD S-XIII, SEA IV and Sopwith Camel fighters; Breguet 14, Voisin X, Caudron R11, Farman F-60 “Goliath”, Vickers Vimy and Caproni Ca.3 bombers, as well as smaller batches of yet more models. The next month, this newly augmented force received its baptism of fire with the Volga Offensive.

[1] After the war, Friedmann joined the Department of Physics at Irkutsk University, where he set to work on refining Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, and elaborated a set of equations that provided a mathematical model for the expansion of the universe. By the end of the 1920s he had revolutionized modern cosmology, whose standard model is named the Friedmann Model after him.

(To be continued...)

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Thomas27

Inscrit le: 13 Avr 2013

Messages: 664

Localisation: Lyon

|

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

pcfd

Inscrit le: 18 Juil 2012

Messages: 152

Localisation: castres

|

Posté le: Mar Fév 10, 2015 21:57 Sujet du message: Posté le: Mar Fév 10, 2015 21:57 Sujet du message: |

|

|

j'aime bien,mais suis trop fainéant pour tout lire en étranger,si tu avais une version française,ce serait top

_________________

Respectez toutes les religions au combat; ne prenez aucun risque quant à votre destination si vous êtes tué. |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Mer Fév 11, 2015 14:52 Sujet du message: Posté le: Mer Fév 11, 2015 14:52 Sujet du message: |

|

|

| pcfd a écrit: | | j'aime bien,mais suis trop fainéant pour tout lire en étranger,si tu avais une version française,ce serait top |

Ah, malheureusement, c'est tout dans la langue de Shakespeare.

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Mer Fév 11, 2015 14:54 Sujet du message: Posté le: Mer Fév 11, 2015 14:54 Sujet du message: |

|

|

La suite...

Although other Entente countries also sent forces to the Russian theater—often with vague or even contradictory mission statements—, on the Siberian front the presence of aircraft flying under other colors than those of the PSG or China remained anecdotal. The air assets deployed by the Japanese were mostly kept in or near Vladivostok as a symbolic display of power, with some sent over to Petropavlovsk in the wake of the Tang-Hara Agreement on the delineation of Chinese and Japanese areas of influence in Eastern Siberia. Britain focused its attention on the Southern Whites, whose air force was reinforced with the RAF 47 Squadron from April 1919 to October 1920, and to a lesser extent on the Northern ones at Arkhangelsk and Murmansk. The only other power which intended to deploy aircraft in support of its ground forces on the Siberian front was France, but organizational mishaps caused the pilots, a squadron’s worth, to arrive in Vladivostok in February 1919 without their planes or ground crew. Following a deal with the French Military Mission, they were assigned to the Chita Flight School as instructors. One of them was Joseph Kessel, already a seasoned veteran at not quite 21 years old—born in a Jewish Russian family and having grown up in Orenburg before moving to France, Kessel had volunteered for a Siberian tour of duty out of what he later described as an atavistic call: “To the eyes [of my comrades], Siberia was nothing but a frozen, godforsaken wasteland… Me, in a sort of trance, I journeyed across unknown continents and oceans. The longer the way, the richer its promises. And at its conclusion, at the end of the world, these endless snowbound steppes, these giant rivers, these limitless forests, these stone age tribes, and the Cossacks from the Baikal, the Amur.” (Les Temps Sauvages) With a wink and a nod from the French Military Mission, Kessel and his fellow pilots would also get to fly combat sorties with PSG aircraft, though mostly in mopping-up operations against remaining Red partisans in the Transbaikal.

Two future major figures of Chinese aviation joined the Expeditionary Corps in time for the offensive: Zhu Binhou and Yang Xianyi. Zhu, also known as Etienne Tsu, was the son of Shanghai business tycoon Zhu Zhiyao (Joseph Tsu). He had gone to France in 1913 to get a pilot’s license and fought in the war as a Foreign Legion fighter pilot; he would later found the Huanlong corporation, one of China’s main aircraft manufacturers. Yang, who was born in the Chinese community of Hawaii, had graduated from the Curtiss Aviation School and come to China in order to join the CAF in January 1919. He would replace Rong upon the latter’s premature death in October 1919, and after the end of the Siberian Campaign, succeed Feng as commander of the CAF.

The offensive was intended to encircle Bolshevik positions to the South and allow a link-up between the PSG’s forces and those of General Markov, nominal leader of the White movement, which held the Don and Kuban regions of Southern Russia. It marked the beginning of large-scale aerial contribution to the fighting. Until then, as on other fronts of the Russian civil war, aircraft were being mostly used for observation, tactical bombing, and ad hoc air support; only a handful of air-to-air engagements had yet taken place, because of the small number of fighters available to either side. But in the preceding months, the Chinese Expeditionary Corps and the PSG’s army had beefed up their air components, and had begun empirically developing a doctrine for their use. Due to the huge size of the theater of operations (stretching across thousands of kilometers of endless steppe), the highly mobile nature of the fighting and the thinness of logistical chains, bringing together the sort of concentration of artillery fire that had made and unmade battles during World War One was virtually unfeasible; instead, Sino-White forces were learning to rely on aviation as a form of surrogate artillery, called on to provide air support of an increasingly closer kind (as a joke went among PSG pilots, “How do you know air support is too close? when it’s our own troops that are firing back!”). The initially cumbersome communication system between ground and air forces was streamlined by providing infantry down to the regiment level direct field telephone lines to specific squadrons, allowing for faster feedback—an evolution that was not entirely welcome by the higher echelons of both PSG and Expeditionary Corps aviations, where there was (reasonable) concern that it created a risk of short-circuiting them out of the chain of command; months of trial and error were necessary to work out a satisfactory procedure. However, given that the industrial and demographic heartland of “Sovdepia” was quite out of range, Sino-White air doctrine gave little consideration to strategic bombing; in the following years, the Chinese would along with Western powers be influenced by Giulio Douhet’s theories, but the Yakutians would hold fast to the idea that the main role of aviation is to support, and act in coordination with, ground forces.

Chinese and PSG pilots also discovered the hard way that their most bitter enemy in Siberia wasn’t the Bolsheviks, it was nature itself. The extreme weather caused the fragile structures of the wood and fabric aircraft to wear and tear much faster than in milder climes; the spring and autumn rasputitsa turned airfields into useless muddy quagmires; fog could keep aircraft grounded for weeks at a time (a place like Irkutsk has an average of 103 foggy days a year). But mostly, it was the cold that pilots learned to fear most. Temperatures in the brutal Siberian winter get so low that aircraft in the open had to keep their engines continually running, lest motor oil congeal into molasses-like jelly—and that was at ground level. Up in the air rubber was liable to turn brittle and crack, rivets to fall off their holes, flight instruments to seize, and wings to become coated with a layer of ice that might grow thick enough to send planes spiraling down out of control. Hypothermia and frostbite were frequent occurrences, despite the introduction in 1919 of British- and US-made electrically-heated flight suits (powered by a wind-driven generator), and among both flying personnel and ground crew, many finished the war with missing fingers and toes. For every airman lost to enemy action, three or more died from environment-related causes.

On the Sino-White side, nearly 250 aircraft were assembled for the Volga Offensive, in support of two Armies, four Cossack cavalry divisions, and a Chinese infantry division. The opening shots were fired on 10 March 1919 and, from day one, aircraft were used extensively to harass enemy formations ahead of advancing Sino-White forces and bomb fortified points. The second week of April brought two high feats for the Sino-White aviation. On 8 April, in front of Saratov, Red commander Boris Dumenko’s Combined Cavalry Division was destroyed in a mere few minutes by bombs and machine gun fire from six Sopwith Camels: the 5,000-strong force lost 600 dead (including Dumenko himself) and another 2,000 wounded, the disorganized survivors being later picked off by cavalrymen from the Orenburg Cossack Division. Two days later, as the fighting had moved to Saratov itself, over 60 aircraft conducted a deadly hours-long strafing noria against the Red Volga Flotilla, sinking or damaging nearly half of its 40-odd vessels and preventing it from effectively contributing to the defense of the city.

However, the Volga Offensive also brought a hard lesson about the limits of air power. Despite initial victories, the Sino-White forces were pushed back in a series of vigorous counter-offensives beginning in early May, and by July had been forced to retreat all the way to their starting point. The Chinese Ninth Division, which had found itself cut off, ran out of supplies and, despite desperate attempts by Rong and Shangin’s men to provide air support, was cut to pieces by Bolshevik forces. Improvised attempts to air-drop supplies had also proved almost entirely ineffective. The sobering conclusion was clear: air superiority alone did not guarantee victory; that remained a job for ground troops as it always had. At a strategic level, the failure of the offensive also convinced General Jiang Chaozong, commander of the Chinese Expeditionary Force, that his supply chains had become critically overextended, and the decision was taken to conduct no further offensive operations west of the Urals. General Khanzhin had come to the same bitter conclusion (and so had Horvath, who was beginning to see the silver lining of an eventual stalemate against the Bolsheviks), and both Chinese and PSG troops pulled back to the Tobol, where they took advantage of a lull in the fighting to entrench themselves.

***

Between August 1919 and November 1921 the Sino-Whites set up five successive defensive lines—across the Tobol, the Ishim, the Irtysh, the Upper Ob, and eventually the Yenisei. In the first four cases the purpose was to wear down the Red Army by forcing it into costly assaults against reinforced positions, only for the defenders to pull back once the line was breached. In this strategy of attrition, aviation had two unglamorous but important assignments: on the one hand, weaken the Red logistical chain through tactical bombing of railroads, rail yards, warehouses and other infrastructure not already destroyed by retreating ground troops; on the other, harass the troops themselves by strafing columns on the march and laying suppressing fire in front of defensive positions. Since, in their retreat, the Sino-Whites were careful to thoroughly destroy the tracks and bridges of the Transsiberian Railway, the one railroad across that part of the country, the airmen’s role in practice was to make it as frustratingly slow as possible for the Bolsheviks to rebuild it.

The Bolshevik military leadership, which still struggled with a chronic shortage of aircraft due to the international embargo and the slow collapse of their industrial base, had opted for a policy of concentrating what planes they could scrounge at the points of greatest need, even if that meant entirely depleting other front of their air assets. This meant that, as long as they were also fighting the Northern, Northwestern and Southern Whites, the Poles and the Ukrainian Anarchists, they seldom had a chance to spare any airplane at all for the Siberian Front, leaving the Chinese and the PSG to enjoy undisputed mastery of the skies for months at a time. Then all of a sudden up to a couple hundred Red aircraft might show up over the front, but they were as often as not fitted with worn-out engines and flown by undertrained pilots—lack of training among Red pilots resulted in one crash for every 10-15 hours of flight time in 1919. Unlike the Sino-Whites, who could purchase new materiel at will, the Reds had to make do with the same aging aircraft types since 1917, some of them imported before the Revolution, some domestically manufactured: in the course of the war, they managed to build some 700 planes in six small preexisting factories, but only some 290 engines, compared with 1,600 planes and 1,800 engines which were jury-rigged back into working condition. Air superiority in both quantitative and qualitative terms allowed the Chinese and the PSG to keep otherwise obsolescent types in operation, using them in patrol or ground attack roles, while the newer ones were held in reserve for those times when the Red air force showed up. In the latter case, technological edge and larger numbers made aerial combat an increasingly one-sided affair.

Various new ground attack tactics were developed during that phase of the war. One that proved particularly effective was devised by Captain Pavel Argeyev, a veteran of both the Western and Eastern Fronts who had arrived from France in June 1919 to join the fight against the Bolsheviks. As a former infantry officer, he had noticed the psychological effect of fléchettes, 15-cm steel darts dropped hundreds at a time from aircraft against massed enemy formations in the early phase of WW1. Invented by the French and quickly picked up by the Germans, the weapon had stopped being used by 1916. Argeyev had the idea of associating the fléchettes with classic antipersonnel bombs, with the delivery system being two aircraft (usually Breguet 14) flying in tandem, one dropping the bombs and the other the fléchettes: to protect themselves against the former, enemy infantrymen had to drop to the ground, which made them more vulnerable to the latter. Late in the war, PSG pilots perfected a night bombing tactic that involved stopping the engine so that their planes would glide silently towards their targets, at which point they would release the equally silent fléchettes. The actual impact was often small, but as psychological warfare this was fairly effective, as Bolshevik soldiers spent their nights fearfully trying to pick up the faint, telltale sounds of a surprise fléchette attack: the whistle of air from the incoming aircraft’s bracing cables, the hiss of the steel projectiles falling to the ground, the sudden cries of comrades pierced through as they lay sleeping. PSG air forces used extensively in a ground attack role the Caudron R11, which had originally been designed as a bomber escort but proved very effective for low-altitude harassment of enemy troops, thanks to its five machine guns. They were also fond of the Voisin X, a largely unsuccessful type on the Western Front, but which proved its worth in the Siberian theater: a very literal form of flying artillery, this pusher single-engine light bomber came equipped with a Hotchkiss 37mm or 47mm cannon, which allowed it to disable armored trains with just a few well-placed shots. Sino-White airmen further learned to concentrate their fire on the rear of Red troop concentrations, were Cheka officers were deployed to keep the regular soldiers moving forward at gunpoint: once the former were down, the latter became much more likely to stall in their advance or even to rout.

In March 1921, Crimea, the last White bastion in European Russia, fell to the Bolsheviks. Some 150,000 Southern White soldiers, officers, officials, supporters and their relatives were evacuated to safety aboard the remnants of the Black Sea Fleet. With the collapse of Markov’s government, Entente powers agreed that the fleet was now the responsibility of the PSG—mostly to save themselves the headache of taking in more White refugees. Nearly half nonetheless vanished when the ships arrived in Alexandria, taking their chances with colonial British authorities to attempt and make their way to Europe, but the rest decided to stay on and see what fate had in store for them in Siberia. Among the influx of Southern White talent that reached “Happy Horvathia” in the aftermath of Crimea’s fall, whether sailing with the fleet or arriving individually, were a number of men who would later play a part in the history of aviation in Yakutia: pilots and officers Boris Sergievsky, Aleksandr Kovanko, Mikhail Safonov and Timofei Borovoy, as well as air transport pioneer Vasily Yanchenko, but one may also include aircraft manufacturers Artur Anatra, Dmitry Tomashevich and Fyodor Tereshenko among them.

(To be continued...)

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Urbain Mukanga

Inscrit le: 06 Jan 2015

Messages: 537

Localisation: Aix-en-Provence

|

Posté le: Jeu Fév 12, 2015 11:31 Sujet du message: Posté le: Jeu Fév 12, 2015 11:31 Sujet du message: |

|

|

Intéressant comme récit mais pourquoi est-ce écrit en anglais? Pour des raisons pratiques?

_________________

Legio Patria Nostra-Honneur et Fidélité |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Thomas27

Inscrit le: 13 Avr 2013

Messages: 664

Localisation: Lyon

|

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Jeu Fév 12, 2015 13:55 Sujet du message: Posté le: Jeu Fév 12, 2015 13:55 Sujet du message: |

|

|

| Thomas27 a écrit: | | Je suppose que c'est parce que son histoire est née sur AH.com qui est un site anglophone. |

Tout à fait. C'est un projet qui en est à sa 11ème année, je ne sais pas s'il faut y voir de la persévérance ou de la lenteur. Sans doute un peu des deux.

Suite et fin de la 1ère partie:

Artur Antonovich Anatra, the grandson of an Italian engineer who had emigrated to Russia in the early 19th century, was already a wealthy banking tycoon when he also became an aviation enthusiast in his late 30s. The founder of the Odessa Aero-Club and publisher of an aviation-oriented illustrated magazine, he offered in October 1912 to set up aircraft manufacturing facilities for the Russian military on club grounds. The first Army orders came in June 1913, for five license-made Farman IV airplanes. In the following four years, Anatra produced more French aircraft under license (Farman, Morane-Saulnier, Nieuport and Voisin) but also, from 1915, locally designed models by French engineer Elysée-Alfred Descamps and Vassily Khiony. By early 1917 most of the output consisted of local designs, namely the Anatra D and DS, and a second factory had been set up in Simferopol, for a total production of some 100 aircraft a month.

One promising prototype that was developed in 1916 by Descamps and Khiony was the Anadva, an innovative design which consisted of two Anatra D fuselages joined by a common wing, with a nacelle attached to the upper wing between the two. The pilot sat in the left fuselage, the observer in the right one, and the gunner in the nacelle. A later version had a crew of six. Flight tests started in July 1916 with pair of 100 HP Gnome-Monosoupape engines, but those were replaced on the second prototype by 140 HP Salmson's. Trials took place throughout 1917. The Russian army saw the aircraft's potential as a light bomber, and 50 were ordered to compensate supply shortages of the Sikorsky Ilya Muromets. However, by then the October revolution had taken place.

After the Bolshevik coup, the company refused to submit to demands of the Council of People's Commissars that its management be turned over to its workers, and was nationalized by decree in December. The following June, the factories were destroyed in order to deny their use by White forces which were advancing on Odessa. Distraught, Anatra left with Descamps on a French ship shortly before the recapture of Odessa by the Bolsheviks in 1919 (Khiony opted to stay behind and later joined the Soviet aircraft industry). Having been informed by representatives of Horvath's government that some of his assets—invested in the Commercial Bank of Siberia—had been salvaged, he accepted their invitation to relocate in Eastern Siberia.

In 1920 he settled in Irkutsk, joined by Descamps, and started an aeronautical workshop that soon began churning out Breguet 14 light bombers, SPAD S-XIII fighters and DS observation planes in modest but steadily increasing numbers. One of his test pilots was none other than his sister-in-law Yevdokia, one of the first women to obtain a pilot's license in prewar Russia. Due to the unreliabilty of local supply chains, Anatra Aircraft Company went for vertical integration, producing itself most component parts, though he remained temporarily dependent on imported French powerplants. By mid-1921 it produced some 20 aircraft a month, a far cry from its heyday in Odessa but a respectable output given the prevailing conditions. Under Descamps' direction, the company resumed the development of its own designs, above all the Anadva. A third prototype was built, this time using 160 HP Salmson engines and with a crew once again reduced to three, and with Horvath's government expressing interest, 13 production models followed, seven of which were deployed in time to take part in the Battle of Krasnoyarsk. However, further orders were cancelled in early 1922, when the armistice with the USSR resulted in cutbacks in military spending.

The engineer in charge of organizing Anatra's powerplant assembly facility was Aleksandr Kvasnikov. Born in Baku in 1892, he studied at the Superior Technical School in Moscow, and was a student of Russian flight pioneer Nikolay Zhukovsky. From 1914 to 1917 he was a military pilot. After the February Revolution, having been demobilized, he enlisted at the Tomsk Technological Institute and graduated in 1918. He joined the White retreat to eastern Siberia; ending up in Irkutsk, he applied for a job with Anatra. Thanks to his qualifications he was swiftly hired.

***

The last major battle of the war was also its largest air battle: on 9 November 1921, began the engagement variously known as the Battle of Krasnoyarsk or the Battle of the Yenisei, during which three Bolshevik Armies tried to breach the Shoshin Line, an elaborate defensive work on the eastern shore of the Yenisei. Since September, with victory achieved or in sight in Ukraine and Central Asia, the two other still active theaters with the Siberian Front, the Reds had deployed nearly every fighter and bomber in their inventory against the Sino-Whites; even then they were still outnumbered more than three to one by the PSG and the Expeditionary Corps’ combined 550 combat aircraft. Throughout September and October, Red pilots had had to fight tooth and nail to dispute air superiority to the Sino-White ones who maintained constant pressure on advancing Bolshevik forces, seeking to maximize attrition before they reached the Shoshin Line. They and their machines were given no respite, having to fend off hit-and-run tactical bombing raids or engage in dogfights on a daily basis, so that their combat effectiveness had seriously decreased by the time the actual battle began. For the next two weeks, as ground forces vainly attempted to breach or turn the artillery-laden fortifications that cut them up to pieces, air forces waged an equally hopeless fight against an enemy that was more numerous, better equipped, in better shape, and with a shorter and intact supply chain. With the Red air forces soon overwhelmed, PSG and Chinese ones could focus on ground targets, strafing and bombing with abandon, defying scattered AA fire. These attacks were all the more devastating as, with the ground frozen, troops were virtually unable to dig in for protection; and the Yenisei, its surface ice broken up by explosions, formed a kilometer-wide moat on which rafts and other small vessels could be easily picked off. With the airfields a short distance behind the Line, the airmen could conduct several sorties a day, reloading and filling up before taking off again. While these tactical ground attacks were going on, the heavier bombers (Farman F-60, Vickers Vimy, Caproni Ca.3 and a few locally-made Anatra Anadva) conducted raids along the Red rear echelons, in some cases all the way to Novonikolayevsk 650 km to the West. In this regard aviation was instrumental in slowing, and then stopping, the Red Army’s eastward momentum.

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Thomas27

Inscrit le: 13 Avr 2013

Messages: 664

Localisation: Lyon

|

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Ven Fév 13, 2015 13:27 Sujet du message: Posté le: Ven Fév 13, 2015 13:27 Sujet du message: |

|

|

1922-1935

After the armistice and the official declaration of the country’s independence in March 1922, the former Provisional Siberian Government, now the government of Yakutia, found itself with an oversized Air Force: the end of the war meant that it was no longer necessary to maintain such a large aircraft inventory, and hundreds of planes were demilitarized and either transferred to civilian administrations or sold off on the open market. The result was a glut of surplus aircraft, to the point where the cheaper models could be bought for less than the cost of a car—by 1923 there were, in fact, nearly as many privately owned planes in the country as there were privately owned cars (admittedly, the rate of car ownership was quite low).

With the large number of surplus aircraft dumped on the private market after the end of the war, many former military pilots returning to civilian life, and a near-complete regulatory vacuum, several air transport companies sprang up in a couple of years, often consisting of nothing more than a single aircraft, one or two pilots, and half a dozen employees; many were in operation for a mere few months before closing down shop, frequently because of a fatal crash. The first such company in Yakutia was Baikal Air Transport, founded by veteran pilot Vsevolod Marchenko: beginning operations in May 1922, it conducted chartered flights between Irkutsk and Lake Baikal with two Breguet 14 converted into the civilian “Salon” version (with an enclosed cabin with comfortable seating for two passengers) and equipped with floats. In April 1923 it began the first regular air service between Irkutsk, Deede-Ude and Chita with a Farman Goliath refitted for passenger transport at the Anatra factory, and was renamed Transbaikal Air Transport. In July 1924 it extended its operations to Harbin, becoming the first Yakutian air line to conduct international flights. However, by 1925 it was facing financial setbacks, and was absorbed into Boreal Air Lines, founded in 1923 by Aleksandr Dattan, the son of Russo-German businessman Adolf Dattan: taking advantage of new regulations that advantaged larger companies and with funding from Kuns & Albers, Boreal Air Lines was able to buy out struggling competitors.

Two of the administrations that made intensive use of aircraft were the Yakutian Post Office, whose Air Service began operations in 1925, and the Aerial Reconnaissance Service, set up in the first summer after independence. The Yakutian government had indeed realized early on how much of the huge country’s territory was barely mapped: although it was the size of Canada, it had under Russian rule received little attention from topographers beyond the coastlines, the main landmarks and the areas of settlement, making it the least-known region in the Northern hemisphere. Further, with a single railway—now renamed the Transyakutian—and few roads, many towns and villages were only linked to the outside world by precarious trails through wild taiga, a situation that, it was hoped, could be remedied with aviation. The ARS gave many non-urban Yakutians their first-ever sight of an airplane, as its rugged machines—flown by equally rugged pilots—crisscrossed the country to fill in gaps in the maps, landing on frozen lakes, sharing the hospitality of awed villagers, and helping create a sentiment of shared national community.

The director of the Aerial Reconnaissance Service during its early years was Viktor Pokrovsky, a driven, no-nonsense veteran of both WW1 and the Southern and Siberian Fronts of the Russian civil war. A controversial figure, Pokrovsky was admired and feared in equal measure by his men, from whom he didn’t tolerate any weakness or mistake; several otherwise excellent pilots were laid off for failing to live up to his exacting standards, and several others died in air crashes because he had instructed them to take off regardless of inclement weather. Yet, to the people taking part in it, it felt like a collective adventure, a feat of endurance and bravery that collected its toll in injury, frostbite and the occasional fatal crash. As every time a small group of people goes through shared hardship for a common goal, a strong esprit de corps quickly developed, and the ARS, within months of its foundation, felt to its members almost like a family (sometimes literally so, as more than one of the women employed for clerical work would bear a pilot’s child, with marriage vows optional and the father’s identity not always certain). The pilots tended to be ethnic Russians, since few non-Russians could learn to fly before and during WW1, but there were also a couple of Jews, Czechs, and a native Siberian or two; the ground crew and administrative staff were much more representative of Yakutia’s ethnic diversity. By January 1925 the ARS had become a well-oiled organization, with highly experienced pilots who knew every last nut and bolt of the machines they flew on (to while away the time on snowbound or stormbound days, the pilots engaged in indoor “races” that involved fixing a broken-down aircraft using as little time and equipment as possible).

Since their surveys took them above barely-explored regions, ARS pilots would occasionally claim to have seen strange sights, from eerie lakes that didn’t freeze over in the winter to sinkholes that weren’t there a month earlier, and many a weird moving light glimpsed in the Arctic sky was dismissed, not always convincingly, as an aurora borealis. Any overflight, whether deliberate or unintended, of the Tunguska impact site was considered especially bad luck. ARS pilots testified to the press that they had seen, in the Vilyuy River valley, strange metallic domes protruding from the ground; although they were unable to produce photographic evidence and attempts to reach these structures by land were unsuccessful, the story, suitably sensationalized, introduced the so-called “Valley of Death” to the general public, creating a sustained interest for paranormal theories that would later become a well-established staple of Yakutian pop culture (Yakutia has more alleged UFO sightings per capita than any other country except the US and is the birthplace of Star Cradle, a fast-growing cult based on alien worship).

Because of the dangerous nature of their job, the pilots would develop various idiosyncratic superstitions and rely on a mishmash of quasi-religious rituals to ward off bad luck. Aircraft were routinely blessed by Orthodox and Buddhist priests as well as shamans, and no cockpit was complete without a few amulets and good-luck charms, regardless of the pilot’s religious affiliation. Pilots objected to having their picture taken in front of their aircraft prior to the flight, as it was considered unlucky; nor would they use the word “last”, and instead use a less inauspicious synonym like “concluding”. A cigarette lit before take-off would only be smoked halfway through, and finished after landing (this also served a practical purpose: due to the risk posed by flammable fumes emanating from aircraft engines, it was best not to have a lit cigarette when climbing onboard). Many pilots also didn’t write the destination in the logbook until they had safely arrived.

The ARS’s fleet mostly consisted in former light and medium bombers of French or British design imported by China during the Siberian Campaign and donated to the nascent Yakutian Air Force. Decommissioned in 1922, they were transferred to the newly-created ARS and specially modified for their new job, with the weight gains from removing the armament used to install larger fuel tanks and reinforce the structure. In particular, long-range surveys were conducted with Vickers Vimys modified along similar lines to the one used by John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown for their 1919 crossing of the Atlantic. These machines carried 3,900 liters of fuel, which enabled them to remain airborne for up to 16 hours; they were powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle Mk. IX engines, a highly reliable in-line powerplant that developed 360 HP and allowed a cruise speed of 185 km/h, with a practical ceiling of 3,700 meters. The configuration of the aircraft allowed the pilots to conduct in-flight reparations on the engines, by stepping out of the cockpit and onto the lower wing (though for obvious reasons it was a highly hazardous procedure). ARS aircraft could be fitted interchangeably with wheels, skis or floats depending on the season and whether they’re using lakes or solid ground for taking off and landing. Typically, a first trip to an unequipped location was done with floats, and only after a landing strip had been installed were wheels preferred. In the winter, with frozen bodies of water providing natural runways, skis were used in all situations.

Because the open cockpits exposed the pilots to the elements, they had to wear heavy insulated or electrically heated flight suits, and carefully cover their faces in order to avoid frostbite and potentially fatal hypothermia when flying in the Siberian winter. Flight instruments were liable to ice up at low temperatures, which required the pilots to guesstimate their speed and altitude as best they could (“dead reckoning”). At night or in cloudy conditions, this could result in dangerous navigational errors if careful attention was not paid, especially at Arctic latitudes where magnetic phenomena mess with compass and make radio communication difficult. As a result, experienced pilots learned to rely more on their intuition than their instruments; the ones whose intuition proved wrong were never found again.

***

The ARS made international news in January 1925 with the famous “Flight of Mercy” to Nome, Alaska. The previous January, the town had reported a fatal outbreak of diphtheria and called for an emergency delivery of antitoxin, but only one, inexperienced pilot was present in the Alaska Territory, and the only three available aircraft had been disassembled for the winter. The Alaska Board of Health was reviewing its limited options and was even considering the far-fetched option of delivering the serum by dogsled when Anton Dobkevich, the Yakutian consul in Juneau, was informed of the matter via an editorial by William Fendtriss "Wrong Font" Thompson, publisher of the Daily Fairbanks News-Miner and a vocal aircraft advocate. Dobkevich cabled Josef Loris-Melikov, the Yakutian Foreign Affairs minister, enquiring about the feasibility of a serum delivery from Yakutia. Loris-Melikov, enthused by the idea, asked Transports minister Boris Ostrumov how to implement it; Ostrumov entrusted the mission to the ARS, which was to pick up 2.2 million units of serum in Irkutsk (almost the entire stock available in the city’s hospitals) and transport them to Nome, with refueling stops in Yakutsk and Kagyrgyn on the Bering Sea. On January 25, Loris-Melikov informed John Dyneley Prince, the US ambassador to Yakutia, that his government pledged to deliver the serum within four days, hopefully in time to stem the epidemic.

Pokrovsky assigned two teams to the job, each flying a Vimy with one half of the precious serum—a single aircraft could easily have carried the whole load, but given the extreme danger involved in long-distance flight in the middle of the Arctic winter (and this one was the coldest in 20 years), he wanted to spread the risk. The four pilots were Timofei Borovoy and Leonid Efimov on the one hand, and Mikhail Safonov and Ivan Smirnov on the other. Borovoy had become a pilot for the Russian military in 1913 and joined the Southern Whites during the Russian civil war; after the evacuation of the last Crimean holdout in 1920, he had gone to Siberia to continue the fight with Horvath's army, then worked for two years as a flight instructor before joining the ARS. Efimov, an aircraft mechanic during his military service in Siberia in 1911, had learned to fly in 1913, become a fighter pilot during WW1; captured by the Germans in 1917, he had joined the PSG’s air forces after his liberation, and eventually become one of the first pilots in the ARS. Safonov, who had been one of Russia's first aeronaval pilots, had fought over the Baltic during WW1, and after the fall of the Tsarist regime had successively joined the Finns, the Southern Whites, and lastly the Siberian Whites; he had enlisted at the ARS in 1923. Finally, Smirnov, the youngest of the four at 29 years old, had become a pilot in 1915, left Russia in late 1917 for Britain where he had worked as a flight instructor, fought for various White armies and eventually joined the PSG, enlisting at the ARS upon its creation.

The aircraft, which had been readied overnight, took off from Irkutsk at 10 a.m. on January 26. At 11 p.m. they landed in Yakutsk for their first refueling stopover. Six hours later, after a short rest for the pilots, they took off in the Arctic night in direction of Kagyrgyn, a 2,340 km flight over the Verkhoyansk chain and, beyond it, the coldest area in the Northern hemisphere. Somewhere over the Anadyr valley, the two planes were caught in a blizzard and lost visual and radio contact with each other. After several endless hours during which they were tossed about and nearly torn to pieces by the fierce, freezing winds, Safonov and Smirnov left the storm behind to find themselves in eerily clear skies, incandescent with the most impressive aurora they had ever seen. “Those gigantic curtains of green and red light were filling the whole sky above us, wave after wave of them” Smirnov would later recall. “At that moment I thought, the Pearly Gates are opening to let someone in. And I knew in my heart that it was for our comrades. Then and there, I realized I would not see them again in this life.” The two men landed at Kagyrgyn with engines practically running on fumes. Their already damaged plane was further shaken up by the rough landing on the small town’s short landing strip. Exhausted, they barely had the strength left to stagger indoors; they fell asleep still wearing their flight suits. When they woke up at 7 a.m. on the 28th, it was to find out that their plane could not take off again without repairs, which in the absence of on-site mechanics they would have to do themselves; and worse still, nobody knew where Borovoy and Efimov were. Since they had long exceeded their fuel autonomy, it meant they had crashed somewhere and, confirming Smirnov’s premonition, were quite certainly dead. The memory of their missing comrades gave Safonov and Smirnov the determination to complete the mission at any cost, and, with the tank of their hastily repaired aircraft refilled, they took off for the last leg of the journey, even as the sun was setting in their backs.

Fortunately, the air over the Bering Sea was relatively still, though the temperature dipped so low that they had to step on the wings and punch holes through the engines’ radiators so the coolant would pour out before it froze. To add to the difficulty, magnetic disturbances made both their compass and their onboard radio useless. Finally, after six hours of flight, they spotted the lights of Nome. They touched down shortly after 8 p.m. Loris-Melikov’s promise had been kept.

The serum delivery made headline news in American and Yakutian newspapers, and Safonov and Smirnov were invited on a goodwill tour of the continental US, though with their battered plane unable to take off again, and no spare parts at hand to fix it, they had to wait until the arrival of the next supply ship, five months later. They and their plane were taken to Seattle, where the latter received extensive repairs, and from there flew to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Minneapolis, Chicago, Cleveland, New York and Washington. They sailed home in September with their crated-up plane and, by November, were back to work at the ARS. In the meantime, their exploit had inspired Nikolay Shavrov, head of the Yakutian Medical Association, to call for the creation of an organization for bringing by air urgent medical assistance to isolated communities; the result was the Yakutian Medical Air Service, which began operations two years later. Smirnov would die in Antarctica in 1931, and Safonov, who had reenlisted in the Yakutian Air Force at the beginning of the war, was shot down by Soviet fighters while flying a reconnaissance plane in 1936. The 1925 serum run was largely forgotten in both Yakutia and the United States until decades later.

In 1959, Chukchi reindeer herders discovered the remains of a plane wreckage in the upper Anadyr valley, which was identified as the unlucky second Vimy flown by Borovoy and Efimov, whose mummified bodies were still in the cockpit. The find brought renewed interest for the event, and the next year it became the topic of a film by Mikhail Romm, “Flight of Mercy”. It was a box-office hit in Yakutia and was released internationally; critics called it “'Night Flight" meets 'The Call of the Wild'”. Romm’s film, in turn, prompted Arkady Pyankov, a Yakutian businessman, to sponsor an air race from Yakutsk to Nome in 1963. The race, known as the Pyankov Run, has been held every January since then.

(To be continued...)

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Archibald

Inscrit le: 04 Aoû 2007

Messages: 9437

|

Posté le: Ven Fév 13, 2015 21:17 Sujet du message: Posté le: Ven Fév 13, 2015 21:17 Sujet du message: |

|

|

| Citation: | | C'est un projet qui en est à sa 11ème année |

C'est marrant, mon programme spatial alternatif (haro sur la navette spatiale !) rentre dans sa septième année ce mois de Février. Hendryk, combien de pages ? J'en suis pour ma part à 732 et des brouettes...

_________________

Sergueï Lavrov: "l'Ukraine subira le sort de l'Afghanistan" - Moi: ah ouais, comme en 1988.

...

"C'est un asile de fous; pas un asile de cons. Faudrait construire des asiles de cons mais - vous imaginez un peu la taille des bâtiments..." |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 15:27 Sujet du message: Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 15:27 Sujet du message: |

|

|

| Archibald a écrit: | | Hendryk, combien de pages ? J'en suis pour ma part à 732 et des brouettes... |

Malheureusement, dans mon cas, c'est beaucoup moins long. Si je rassemble tout ce que j'ai écrit moi-même, ça fait 200 pauvres pages. Peut-être 500 si on inclut les travaux des autres contributeurs, l'essentiel sous forme d'histoires romancées.

On continue:

In 1925, as the Yakutian government began to grasp the potential of aviation to overcome the problems of long distances and underdeveloped transportation infrastructure, the aviation portfolio was detached from the Ministry of Transports and Communications to fall under the purview of the newly-created Air Ministry; however, the fact that the Ministry of Transports kept the management of air mail for itself, and the War Ministry also claimed responsibility for military aviation, would lead to protracted bureaucratic turf wars between the three administrations. Farrukh Gayibov, formerly in charge of the Aviation Department at the Ministry of Transports, was appointed at its head and got to work. Gayibov, an ethnic Azeri, had flown as part of a Sikorsky Ilya Muromets crew on the Eastern Front and participated in numerous bombing raids over Germany and Austria-Hungary between 1914 and 1917, when the February revolution brought strategic bombing operations to a virtual standstill, as ordnance and spare parts could no longer be obtained and many personnel deserted. When the civil war broke out in 1918, Gayibov assembled a few like-minded crewmates and, onboard a jury-rigged Ilya Muromets (its four engines came from three different sources), joined the Southern White forces in Novocherkassk. In 1919 his plane, used as a long-distance liaison between the Southern and Siberian Whites, was irretrievably damaged while landing in Ufa; with the lines of communication increasingly uncertain, he opted to fight on with the Siberian Whites. A colonel by the end of the war, he was chosen by Ostrumov to take charge of aviation-related matters at the Ministry of Transports.

Upon becoming minister in his own right, Gayibov oversaw the construction of proper airports in the young country’s larger cities (Irkutsk, Deede-Ude, Chita, Yakutsk, Ust-Kut and Nerchinsk, as well as Ayan which was the Yakutian Navy's home base); with the Yakutian Air Postal Service created the same year, even smaller towns made sure they had an airstrip and the essential amenities of basic airplane maintenance. Another early initiative of the Air Ministry was to implement the first regulations concerning air transport: it now had authority to designate the air routes, develop navigational infrastructure, register companies, license pilots and aircraft, and investigate accidents. This resulted in a “pruning” of the sector: within a year the formerly anarchic field of air transport in Yakutia had become a de facto oligopoly, with only five companies sharing the market: Yanchenko Air Services, Great Northern, Trans-Yakutia Air Fleet, Plyusnin Air Transport, and last but not least Boreal Air Lines. By the eve of the war, further mergers had reduced the number to three, with Yanchenko having been bought up by Boreal and Great Northern by Plyusnin, while Trans-Yakutia Air Fleet, nationalized in 1934, was renamed Air Yakutia. However, local air taxi services remained in operation all along, in part thanks to a regulatory loophole that exempted companies operating in only one province from the new federal rules; a typical town of more than 3,000 inhabitants would usually have at least one privately-owned bush plane.

***

Despite the Anadva's relative lack of success, Anatra and Descamps were convinced of the basic soundness of the twin-fuselage layout, and in the following years, they developed more prototypes for escort fighters and medium bombers with such a configuration. None entered production, and in the meantime the company kept itself afloat assembling Breguet 19 and other licensed models. It faced an uphill struggle maintaining its share of the small Yakutian market due to the post-war glut of secondhand airplanes, but especially to the competition of Chinese companies, which took advantage of favorable trade arrangements (and resorted to outright bribery when all else failed) to get the lion's share of Yakutian Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard, Postal Service, etc. procurement contracts. Production fell and workforce shrank; several of the company's engineers quit, some, like Irkutsk native Nikolay Kamov, to start their own businesses.

In 1928, joining an international fad for large multiengine passenger aircraft, Anatra began work on the A-6. Like previous designs, it had twin fuselages (with room for 16 passengers each), with the cockpit located in the left one. The first all-metal plane by Anatra, it was powered by five Gnome-Rhône Jupiter radial engines, one in each outer wing, one in the central wing, and the other two at the front of each fuselage. Boreal Airlines pre-ordered three, but by the time the first one was delivered in 1931, the world was in the midst of the Great Depression and the company, facing financial hardships, had to cancel the purchase of the other two. Further, although the aircraft had decent performance with a cruise speed of 190 km/h and a range of 980 km, it turned out to have high operating and maintenance costs due to its complex layout. As a result Boreal Airlines grounded it after just a few months. In late 1933 it was purchased by the YAF, which used it as a VIP transport and, after the beginning of the war, sent it on morale-boosting tours throughout the country. After being damaged in a hard landing in 1936, it was decommissioned and scrapped.

Prospects looked up for the company even as they grew gloomier for the country in 1933. With war an increasingly likely possibility, the Yakutian government engaged in a policy of rearmament, and with Chinese companies busy with China's own military program, it placed larger orders to Anatra, in particular for the A-9 heavy fighter then under development. The latest of Anatra's twin-boom designs, the A-9 was an all-metal monoplane two-seater with cantilever wings, fixed landing gear, a fully enclosed cockpit, and a versatile weapon array with machine guns and/or 20 mm cannons concentrated in the nose. This arrangement would result to its being used to great effect as a ground attack plane during the Taiga War.

Born in Kharkov in 1894, Vladimir Bodiansky studied civil engineering in Moscow from 1910 to 1914. He worked as an engineer on the construction of the Bukhara railroad, then volunteered for military duty at the outbreak of WW1. Promoted to cavalry officer in 1915, he became a fighter pilot. After the beginning of the Bolshevik revolution, he went to France and joined the Foreign Legion. He studied at the École supérieure d’aéronautique et de construction mécanique in Paris and graduated in 1920. He left for Eastern Siberia in 1921 and was hired as an engineer on the Transsiberian by Horvath's provisional government. In 1923 his fondness for aviation got the better of him again and he got a job at Anatra, teaming up with Descamps on technical design while Anatra himself focused on the company's general management. His engineering skills were responsible for Anatra being able to start producing the A-12 (the local version of the Arsenal VG-30) in record time in 1940. He succeeded Anatra as director of the company in 1947. As he wrote in his autobiography in 1964, “I was always fond of three things: trains, planes and buildings. My life's blessing is that I was able to devote myself to two out of three. My life's curse is that I was only able to devote myself to two out of three.”

***

Although Anatra was the better-known aircraft manufacturing company in Yakutia, it wasn’t the only one. Shortly after the country’s independence, competition sprang up in the form of a duo, Fyodor Tereshenko and Dmitry Tomashevich. Tereshenko was born in a Ukrainian business family, graduated from Kiev Technical Institute and built his first airplane, the Tereshenko 1, in 1909, based on Blériot blueprints. His aeronautical workshop was the first in Ukraine. His attempt to found an aerodynamic laboratory in Kiev was thwarted by the beginning of WW1, and he moved to France in order to escape the civil war. In 1921 he left for Yakutia, where he set up a workshop in Irkutsk and assembled a few more one-off airplanes for private customers in the course of the 1920s. During that time he became increasingly fascinated with occultism and mysticism, involved himself with Yakutia's thriving spiritual scene, and in 1930 became a disciple of Scriabin. Tomashevich was born in Ukraine from a family of impoverished Lituanian aristocrats who got killed during the Civil War. He left Russia with the Black Sea Fleet and, upon arriving in Yakutia, completed his engineering studies. In 1925 he started working with fellow Ukrainian Tereshenko, and became the de facto manager of the company as Tereshenko devoted more and more of his time to mystical pursuits; in 1926 it was renamed Tereshenko, Tomashevich & Co. (TTC).

In the second half of the 1920s, the aircraft inherited from the War of Independence were beginning to wear out, and TTC sensed a commercial opportunity. The small Yakutian aviation market, to be sure, was largely dominated by imports from China. But, Tereshenko and Tomashevich were convinced, there was potential demand for a general purpose airplane rugged enough to operate from rough and underequipped airfields such as those that dot the Yakutian bush. Such an airplane would have to meet exacting specifications: it would have to be low-maintenance, so that even the most isolated village could keep one in working condition; it would need outstanding STOL capability, in order to be able to take off from small clearings; it would have to be versatile, in order to fulfill different roles with only minimal modifications; and last but not least, it would have to be cheap enough to undercut even bargain-basement secondhand Chinese models.

This was a daunting list, but Tomashevich felt he could meet the challenge he had set for himself (Tereschenko soon started losing interest, though he let his partner proceed). In early 1927 he got to work, using the Potez 25 as a basis. However, he realized that simply mimicking the successful French airplane would result in production costs that would make it uncompetitive, and he went back to the drawing board. By the end of the year he had come up with his own design--a combination of existing, even aging, concepts that nonetheless amounted to more than the sum of its parts. The TTC-5 was a traditional wood-and-fabric biplane with an open cockpit and room for either a passenger or up to 250 kg of cargo. Its powerplant was a 130 hp Salmson 9AB, an unremarkable engine that gave it a respectable range of 740 km but a paltry top speed of 160 km/h. However, the leading-edge slats added to the wings (an unlicensed knock-off of a patented Handley-Page design that would result in protracted litigation in later years) gave it an extremely low stall speed of 58 km/h: it could land and take off from the shortest airstrips and, given a strong headwind, was virtually able to hover in place.

The first prototype flew in April 1928, and the first production models rolled off the TTC factory the following summer. The TTC-5, nicknamed the Baykush (Owl), proved a runaway success, thanks to its low purchasing and operating costs that made it affordable to local communities and private individuals. Government administrations placed orders as well, and TTC built new assembly plants to meet demand. Although sales dipped after 1929, they remained large enough to generate healthy profits despite the idle production capacity. Then after 1933 TTC was one of the beneficiaries of Yakutian rearmament, as a militarized version of the Baykush was developed. It remained in YAF inventories long after its obsolescence as a front-line aircraft, soldiering on as a basic trainer, and some remained in use in civilian service well into the 1960s. A few carefully maintained models can be seen at Yakutian air shows to this day.

The Kamov company, which is to this day a first-tier designer of rotorcraft, was founded by Nikolay Kamov. Born in Irkutsk in 1902, he was among the first graduates of Irkutsk Technical Institute. A brilliant young engineer, he was hired in 1922 by Anatra to oversee the manufacture of variable-pitch propellers. He worked closely with Aleksandr Kvasnikov, who was in charge of powerplants, and began to develop an interest in rotorcraft. When Anatra instructed him to drop that avenue of research (as he reportedly said, “There is no future in wingless aircraft”), Kamov instead resigned and, with the financial backing of the Siberian Commercial Bank, founded his own company in 1928. He assembled several helicopter prototypes, whose potential for observation and short-range liaison caught the attention of the Yakutian Air Force when the incoming Gajda administration launched its rearmament program in 1933. The next year, he began receiving support and technical input from Georgy de Bothezat, director of the Aeronautical Laboraty of the Yakutian National Committee on Advanced Technologies, himself a vertical lift enthusiast: while living in the United States during the War of Independence, he had developed a helicopter prototype on behalf of the US Army. Kamov was allowed to use the facilities of the Aeronautical Laboratory in Kultuk, on the southern tip of Lake Baikal, and with de Bothezat’s help, he developed the prototype of the K-VP, a coaxial helicopter that first flew in 1937 and would be followed by several production versions throughout the latter phase of the war and the early post-war years.

(To be continued...)

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Capitaine caverne

Inscrit le: 11 Avr 2009

Messages: 4137

Localisation: Tours

|

Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 17:05 Sujet du message: Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 17:05 Sujet du message: |

|

|

C'est sympathique et agréable comme travail, le niveau de l'anglais étant des plus abordable. Mais est-ce qu'il serait possible d'avoir quelques cartes, photos ou schémas pour illustrer le propos ?. Le texte à beau être interrèssant, il reste aride à lire.

_________________

"La véritable obscénité ne réside pas dans les mots crus et la pornographie, mais dans la façon dont la société, les institutions, la bonne moralité masquent leur violence coercitive sous des dehors de fausse vertu" .Lenny Bruce. |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Thomas27

Inscrit le: 13 Avr 2013

Messages: 664

Localisation: Lyon

|

Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 17:06 Sujet du message: Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 17:06 Sujet du message: |

|

|

| Hendryk a écrit: |

Malheureusement, dans mon cas, c'est beaucoup moins long. Si je rassemble tout ce que j'ai écrit moi-même, ça fait 200 pauvres pages. Peut-être 500 si on inclut les travaux des autres contributeurs, l'essentiel sous forme d'histoires romancées. |

A oui tu prend ton temps là ^^

En moins d'un an j'en suis plus de 130 pages de texte et d'illustrations ^^ Pourtant je glande régulièrement. J'ai tendance à faire un pause après chaque chapitre.

_________________

Ma boutique : https://www.redbubble.com/fr/people/Artof-ThomasD/shop?asc=u

Mes livres: http://www.amazon.fr/-/e/B0191PGYUE?ref_=pe_1805951_64028601 |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

Hendryk

Inscrit le: 19 Fév 2012

Messages: 3241

Localisation: Paris

|

Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 18:24 Sujet du message: Posté le: Sam Fév 14, 2015 18:24 Sujet du message: |

|

|

| Capitaine caverne a écrit: | | C'est sympathique et agréable comme travail, le niveau de l'anglais étant des plus abordable. Mais est-ce qu'il serait possible d'avoir quelques cartes, photos ou schémas pour illustrer le propos ?. Le texte à beau être interrèssant, il reste aride à lire. |

Je n'ai pas grand-chose en matière d'illustration, mais voici toujours une carte de l'Asie dans les années 1920.

_________________

With Iron and Fire disponible en livre! |

|

| Revenir en haut de page |

|

|

|

|

Vous ne pouvez pas poster de nouveaux sujets dans ce forum

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum

Vous ne pouvez pas éditer vos messages dans ce forum

Vous ne pouvez pas supprimer vos messages dans ce forum

Vous ne pouvez pas voter dans les sondages de ce forum

|

|